Bidirectional violence, a foreword

Before we examine bidirectional violence, it is important to ask: How does a relationship evolve to be abusive? Does it take deliberate acts by one person against another to gain power and control bit by bit?

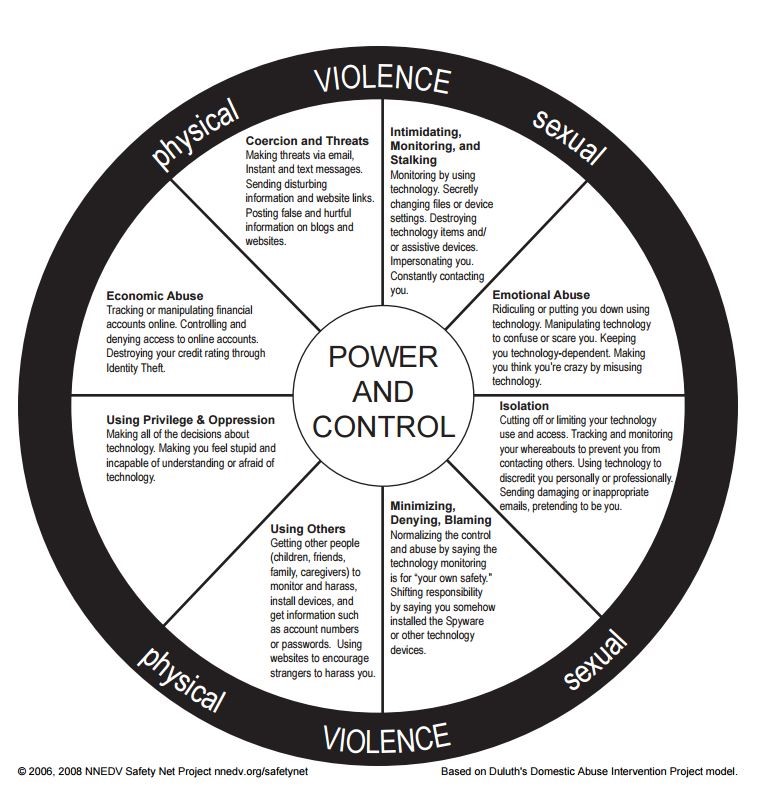

In my view an abusive relationship is every single section of the Duluth Power and Control Wheel:

Intimate Partner Terrorist

Acts of coercion, intimidation, emotional abuse, behaviours aimed at degrading, destroying and humiliating the other person to gain control. How is this control exerted? By the presence, use or threat of physical and sexual violence. Practitioners and survivors may be familiar with the term ‘intimate partner terrorist’ because that is what they are. Holding every person in that home to ransom in exchange for their emotional worth, their self-esteem and any desire to leave.

Three types of Perpetrator

Johnson (2006) after extensive research devised three terms to explain the subtypes of perpetrator that might be seen in intimate partner violence. These three terms include the intimate partner terrorist detailed above, violence resistance and situational couple violence. The term violence resistance denotes victims who in the face of further abuse, use learnt behaviours to protect themselves and behave violently for self-preservation. Differentially, situational couple violence is a term coined to describe toxic relationships in which there is violence but this is not about gaining power and control over the other person. Misunderstanding these terms can drastically increase risks to victims. Johnson himself stresses that the most dangerous of all abuse is intimate partner terrorism, which Aurora asserts is the real essence of what we are naming when we talk about domestic abuse.

The term ‘bidirectional violence’

In recent months, I have seen a new terminology being used. The term bidirectional violence has become common parlance in some multi-agency meetings. The term has been generated to capture relationships in which both parties use violence and/or abusive behaviours to one another. The term suggests that a single primary aggressor cannot be identified. My question then is how would a survivor feel? Particularly those who begin to resist and fight back, knowing that their acts of self-defense, their attempts at protecting themselves, their use of learned aggression against the perpetrator are seen as a balanced form of intimate partner violence?

How a relationship can evolve into bidirectional violence

Imagine knowing the mood of the perpetrator and being able to predict whether it is physical violence, verbal abuse, control tactics or the threat of a sexual assault that is brewing. However, one day out of fear you assault the perpetrator to protect yourself and the children. But this time they contact the police and you find yourself being arrested. The perpetrator actively claims victim status, giving details of all the times there have been other violent incidents. The normal safeguarding won’t apply to you now, because you have been a victim and are now a perpetrator. The perpetrator might get a visit from the safeguarding agencies, who will offer them support. Imagine then, that at the next multi-agency meeting, your experiences of control, psychological abuse, serious physical and sexual violence are reduced to ‘bi-directional’ violence.

What are we really saying? That she is as bad as him? Six of one, half a dozen of another. Frontline practitioners within Aurora would always be of the opinion that attitudes like this are archaic and patriarchal. We absolutely do not condone violence in any form. However, it is important in our work to explore the situation with a survivor who is beginning to fight back. We understand why this might happen, but we plan with them to ensure this doesn’t occur for the future safeguarding of everyone linked to the abuse, including the perpetrator. Some of our advocates have worked with women who have killed their partners in self-defense and the ramifications of this are lifelong.

Most importantly, if we don’t explore, we ignore the voice of the victim. Many survivors of abuse are likely to try and predict the violence, placating the perpetrator and doing what is necessary to avoid more serious injury. What the victim hears is that we do not understand her experiences. We ignore the gendered nature of domestic violence, we don’t delve deeper into the power and control in that relationship and we do not identify who the primary aggressor is. We completely overlook the victim’s experience and buy into the perpetrators narrative about ‘her being as bad as him.’

An example of bidirectional violence mislabelling

To evidence this point home further, January 8th 2018 saw the release of the Domestic Homicide Review into the murder of Katrina O’Hara on 7th January 2016 by her former partner (Mellor, 2018). The first police response into domestic abuse within this relationship was made on 10th November 2015 when both parties alleged they had been assaulted. The victim admitted to throwing some of the perpetrator’s stuff around. Within 58 days of making this report, the victim had been murdered. The DHR review made multiple recommendations but of note was point 6.9 which concluded that the first police attendance was mislabelled. Reviewing Police Officers determined that that the victim was ‘very much the perpetrator’ which changed the course of police responses. Ultimately, the victim’s confidence in the agencies tasked to protect her was undermined and she paid for this with her life.

How should we see bidirectional violence?

Domestic abuse is gendered. It affects disproportionately more women than men; two women die a week at the hands of abusive partners (Brennan, 2016). I urge frontline practitioners to consider this the next time you hear the term bidirectional violence. Use it as an opportunity to educate others and consider investigating further into what is really happening in that home. It’s important to understand that victims don’t generally shout about their victimhood, they minimise the behaviour, they make excuses for the perpetrator. They rarely if ever, shout about the abuse.

One way in which you can assess the legitimacy of counterclaims is to refer to the DYN project assessment ‘identifying legitimate victims’ (Robinson & Rowlands, 2006 pp34-35).

Perpetrators are incredibly good at getting professionals to collude with their behaviour. They can and will be very plausible. Let’s not allow them to use us in their power and control games against victims.

#HerNameWasKatrina

Hayley – Serial and Priority Perpetrator Co-ordinator – Aurora New Dawn – (Domestic Abuse Prevention Partnership (DAPP)).

*Hayley is a qualified probation officer and worked for the National Probation Service for twelve years before joining the Aurora team two years ago.*

Aurora New Dawn

Want to help us raise awareness? Click here to share this page on Facebook

Are you affected by any of the issues mentioned here? If so, please get in touch!

Click here to contact Aurora

Want to find out more about us? Click here to find out more about Aurora

Want to donate to our cause? 💜 Click here to support us!

References:

Brennan, D. (2016). The Femicide Census: Annual report on cases of Femicide in 2016. Women’s Aid Federation.

Katrina O’ Hara DHR

Mellor, D. (2018) Domestic Homicide Review. “Sarah.”

Overview Report. Dorset: Dorset Community Safety Partnership

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence against women, 12(11), 1003-1018.

Robinson, A., & Rowlands, J. (2006). The Dyn Project: Supporting Men Experiencing Domestic Abuse (pp. 34-35). Cardiff.

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.538.716&rep=rep1&type=pdf